Plan All of the Things!

In my previous post, Bad Habits We Learn in School, I touched on the fact that software is notoriously difficult to estimate accurately, and when we are wrong, we tend to be wrong on the side of underestimation (sometimes by as much as 4-6 times!). This is hugely problematic, because severe underestimation is the first step towards late software, which puts you right onto the path of the Vicious Cycle of Software Development. So learning how to increase our accuracy in estimating software is a vitally important skill to develop.

In this post, I want to tackle one common root cause of underestimation: simply forgetting to account for critical work while planning out features or a project. It sounds silly, but it happens far more often than you think.

Feature-level Planning

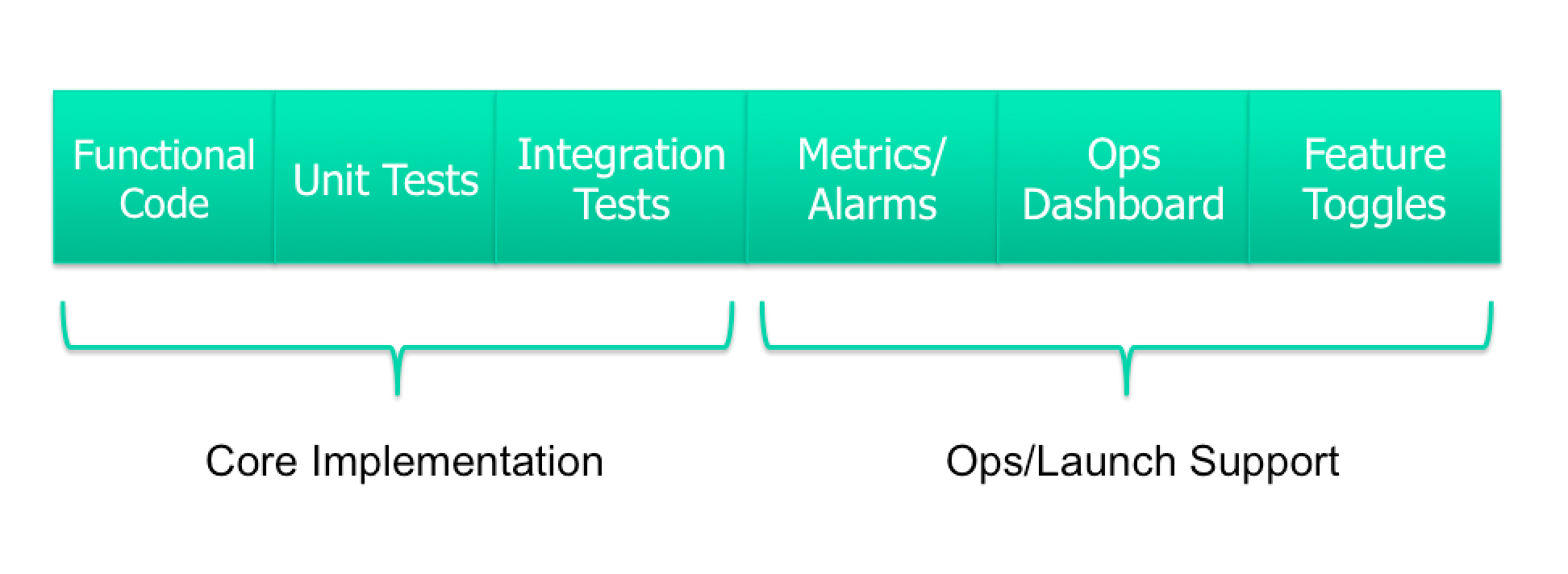

First, let’s start with feature-level planning. When planning the implementation of a feature, it’s important to explicitly take into account all possible aspects. Here’s how I picture the anatomy of a feature:

Not every feature requires all of the above pieces depending on its size and scope. However, I’ve seen teams repeatedly forget to plan for many of the quality measures listed above. Over time this compounds, leading to huge gaps in quality and technical debt that is a hard sell to the business to go back and address after the fact. So planning for quality up front saves you a lot of pain down the road.

Let’s take a look at these pieces in more detail.

Core Implementation

The first major category of a feature is the core implementation, made up of functional code, unit tests, and integration tests.

Functional code is the code that implements the desired feature behavior. Unit tests test your functional code in isolation. Dependencies are mocked allowing for several edge cases to be covered. Unit tests are your first line of quality defense and should never be skipped, because they’re so easy to write. Some teams push for using Test-Driven Development (TDD), which ensures unit tests are always included. I’ve found some developers can be really resistant to TDD, so I side-step that argument by instead having a rule that functional code and unit tests must always be included together in the same commit. You can write the functional code first and then your unit tests or the other way around. I really don’t care as long as they’re both there.

Integration tests are more complex tests where you test your functional code against other system dependencies. There are many flavors of integration tests, such as functional tests, system tests, acceptance tests, etc. For the sake of this post, I’m just using the term integration tests to cover any and all of these kinds of tests. Unlike unit tests, it’s not usually practical to write integration tests in the same commit as your functional code changes. As a result, it’s embarrassingly common to forget to account for time spent writing integration tests when planning your feature.

In recent years, I’ve become a fan of Behavior-Driven Development (BDD) as a means to address this, at least at the acceptance (user-facing) test level. BDD feature files are a nice way to document expected behavior of the feature as a whole, and ensure what you plan to build is what the business is expecting. Since you write feature files up front during requirements clarification, it’s easier to remember to plan for actually implementing all or a subset of them as automated acceptance tests later on.

Ops/Launch Support

The second major category of a feature is operations and launch support, made up of metrics, alarms, ops dashboards, and feature toggles.

Metrics give you visibility into how your code is working in production. I have this as a separate component of a feature, however generally, metrics are something I try to think about and insert into the functional code as I’m building a feature. Automated alarms are used to notify you if your code is behaving outside of normal error or latency thresholds. Ops Dashboards give you an at-a-glance view of the health of your system by displaying key metrics. For major feature launches, it can be very useful to have a dedicated dashboard of key metrics to ensure the feature is working correctly. Smaller features may not require a dedicated dashboard, but you should consider whether this feature warrants adding new graphs to any existing dashboards.

Feature toggles are a way to decouple deployment of code changes from release of a feature. These are flags that are embedded in your functional code, allowing you to silently deploy your feature into production. Then when you’re ready to actually make the feature go live, you toggle the feature on (usually by updating a toggle value in a database). Feature toggles are powerful, because they allow you to nearly instantaneously launch your feature, and–equally important–unlaunch your feature if things go wrong, which is far faster than deploying new code to your production systems. Since you have to write your functional code such that it can work one way with the toggle off and another with the toggle on, it’s important to consider whether this is necessary for your feature and plan for it in advance.

Don’t forget!

One thing I’ve found to help in planning a feature is to use a literal checklist of the above items during backlog grooming/sprint planning to ensure you’re considering which ones are necessary and then explicitly create stories/tasks for them. Similarly, I’ve seen teams who leverage templates in their sprint/issue tracking system include these items in their story templates.

Project-level Planning

Like I said before, routinely forgetting things at the feature-level compounds over time causing huge quality problems. However, there are also similar misses that can happen during project-level planning. At larger companies, project-level planning is often important for trying to determine rough counts of how many people will be needed to deliver a project by a certain date. These kinds of estimates are far less accurate due to the huge amount of ambiguity involved when trying to estimate a project that will take several months. The general strategy is to try to enumerate as many big pieces as you can think of and then give them very rough sizings.

Brainstorming these big pieces of a project is another opportunity to forget to account for major pieces of work that are required. In this case, I find teams generally do a good job of thinking of the features that make up the core customer-facing functionality of their project. It’s the non-customer-facing features that tend to be forgotten. Here are the ones I see get forgotten on a fairly regular basis:

- Disaster planning - For projects with high availability requirements, it’s important to go through a disaster planning exercise where you walk through key dependencies and exposures in your architecture and brainstorm mitigations. These mitigations often involve building some set of tools to help in disaster recovery scenarios.

- Data Backup/Restore - Setting up backup/restore procedures for your datastores is easy to forget, but very painful if you need them and they aren’t there…

- Administrative tools - You may need to build special tooling for product owners or customer service associates to use to handle problem scenarios (process returns/refunds, ban/block misbehaving/fraudulent users, etc).

Again, the above are not always required depending on the size and scope of the project, but it’s extremely frustrating when you need them and realize you forgot to account for them at all and must now scramble with your existing resources to fill the gaps.

Accurate estimation of software is tough for many reasons, but hopefully these tips will help you fight underestimation by at least considering all aspects of features and projects. Do you have anything to add to my lists? Feel free to share in the comments!

Leave a Comment