How to Set the Technical Direction for Your Team

I’ve found that one of the keys to a productive and happy development team is when every member of the team understands (1) the technical direction of the team, and (2) how the work they’re currently doing contributes to that direction. Because of this, one of my key roles as a senior developer is helping teams establish a clear technical direction, as well as a plan for how to get there.

After several years working at Amazon, one thing that continually stands out to me is the genius of Amazon’s Leadership Principles. At some other large companies where I’ve worked, their version of leadership principles or corporate values were just a set of vague statements or buzzwords printed on posters and hung somewhere in the office. Most people ignored them and carried on with their daily work. However, at Amazon, we live and breathe the leadership principles and refer to them frequently in daily conversation. Collectively, they setup a framework for thinking that pushes everyone who works there to become fast-moving, innovative leaders.

When it comes to establishing technical direction for a team, two leadership principles come into play: Think Big and Bias for Action.

Think Big encourages you to “create and communicate a bold direction that inspires results,” while Bias for Action pushes you to move quickly and not get lost in the dreaded analysis paralysis. A good technical direction incorporates both of these principles. As a result, I coach teams that they must establish, both a long-term, directional vision and short-term, incremental milestones that lead in the direction of the long-term vision.

Long-Term Vision

The long-term technical vision is where the Think Big leadership principle comes into play. Take the business problem, put pesky constraints like time and resources out of your mind and try to come up with an idealized architecture. Be liberal with unicorns and rainbows in your block diagrams. 😉

Seriously though, long-term visions are tricky. They have to be clear enough that they are believable and everyone on the team can understand and align to them. They have to be relatively stable over time. Finally, they also have to be abstract enough that individuals feel empowered to forge creative paths to get there. This is a tall order and a key challenge of effective leadership.

Here are some tips that help me when coming up with a long-term technical vision:

- A picture is worth 1000 words. Architectural block diagrams can add a lot of clarity around key components and their relationship to one another.

- Don’t try to fit your entire vision into a single picture. Use multiple pictures at different levels of abstraction to provide clarity. I love Simon Brown’s concept of thinking of architecture diagrams as maps of your codebase.

- Stay abstract. Avoid choosing specific technologies. Instead, stick to defining components and keep concepts like databases, queues, streams, etc generic, rather than naming a particular solution.

- Walk through key business use cases and show how the components interact.

- Enumerate the key business and technical wins of the architecture.

- It’s all about boundaries. It’s critical to define the key subsystems and components of the architecture and their responsibilities. A great way to solidify understanding of responsibilities is to focus on boundaries when walking through use cases. Specifically call out what each side is responsible (and not responsible) for.

- Don’t try to design to the last detail. You don’t need to go deeper than component level, i.e., no class diagrams. Remember, the important thing for long-term vision is defining key components and their responsibilities.

Short-term Incremental Milestones

Long-term visions are important, but if you are really exercising Think Big, you will end up with the outline of a system that will take several years to build. If you just turn around and build that entire system from scratch, you might run out of funding before ever launching. Even worse, you might get to the finish line and realize what you’ve built wasn’t actually the right solution. Businesses shift quickly and you need to be able to adapt to that change. This is where the Bias for Action leadership principle comes into play to balance out Think Big.

Once you’ve established your long-term vision, it’s time to come back to the real world and come up with an incremental plan to get there. That plan needs to involve launching something real to customers quickly so you can get rapid feedback in case you need to course correct in the spirit of Agile and The Lean Startup.

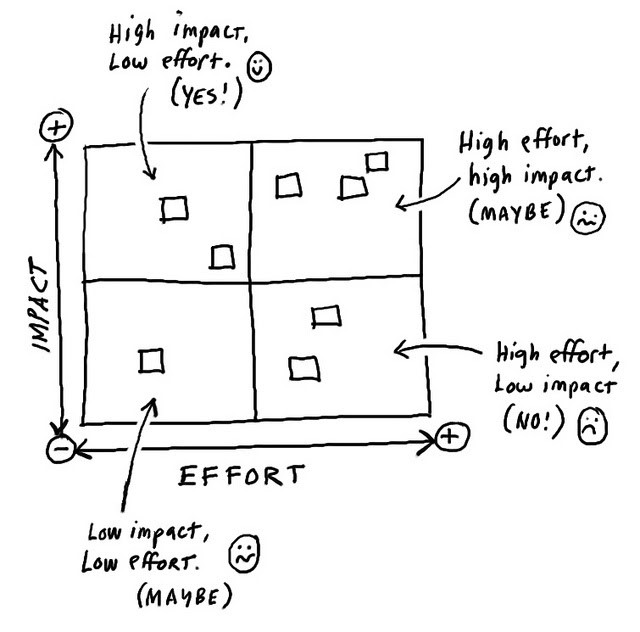

I like to use the Impact vs Effort Matrix as a way to think about this:

Building your long-term vision from scratch should be firmly in the high effort, high impact quadrant. However, to get started, look for tasks in the low effort, medium-high impact area that are in the direction of your long-term vision. For example, your long-term vision may be to build a complex, feature-rich realtime business analytics platform for your business. However a short-term milestone in that direction would be to stand up a Kafka cluster and attach a connector to a replica of a few of your DBs and push updates into an ElasticSearch cluster. Then use Kibana to create a few dashboards. This is something that could be completed in a few months and will give you customer feedback that helps you determine next steps. It can also give you datapoints to help determine if you’re headed in the right long-term direction or if your long-term vision needs to be tweaked.

Here are some tips that help me when coming up with short-term, incremental plans:

- Look for milestones that are achievable within a 3-6 month (or shorter, depending on the size and scope of the project) timeframe. Ideally milestones are customer-facing, but don’t stretch your milestones out to a year or 2 years just to make them customer-facing. If they’re that big, there’s probably a scrappier solution that will give you the feedback you need.

- Be concrete. Unlike your long-term vision, short-term solutions should be well-defined. Choose specific technologies and justify your choices.

- Enumerate the key business and/or technical wins of each milestone. This ensures you know why you’re doing each one.

- Use the long-term vision as your guide post. Your milestones should be in-line with the end goal, although they can veer off track a bit if there are good reasons for it. However, avoid lateral or backward movement.

- Don’t try to define every single milestone all the way to the end goal. The long-term vision is directional and it may (will) change and evolve as you learn more from each milestone. Trying to define every step at the outset is difficult and wastes time.

I can’t stress that last tip enough. I’ve worked with people who try to push for detailed plans that span multiple years, and it just ends up being overwhelming and demoralizing to the team. The thing is, if you start with lower effort work and get some quick wins, it builds momentum and confidence. I also find that as you make progress, milestones in the high effort/high impact quadrant start to shift left. In other words, something you’ve built or learned in a previous milestone suddenly makes another milestone much more achievable. They can become the next milestones on your roadmap, further increasing confidence and momentum. I much prefer this model, because it’s adaptive and decentralized, which empowers teams.

Conclusion

Having a clear long-term and short-term technical direction is critical to leadership in software development. Hopefully this helps give you an idea of how to approach setting technical directions, and how Amazon’s leadership principles can help. If you’re interested in learning more about the leadership principles, I recommend reading The Amazon Way.

Leave a Comment